All official European Union website addresses are in the europa.eu domain.

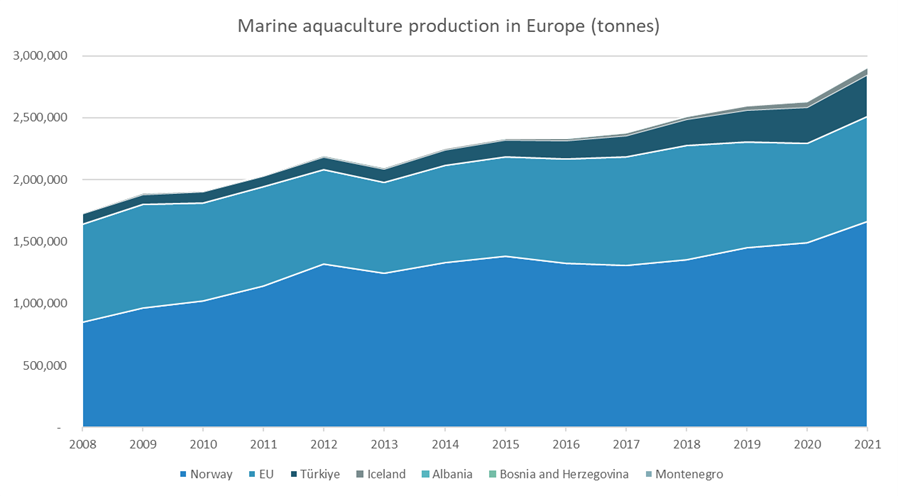

See all EU institutions and bodiesExtraction and cultivation of living resources as a human activity affecting the marine environment includes fish and shellfish harvesting (capture fisheries), marine plant harvesting, hunting and aquaculture.

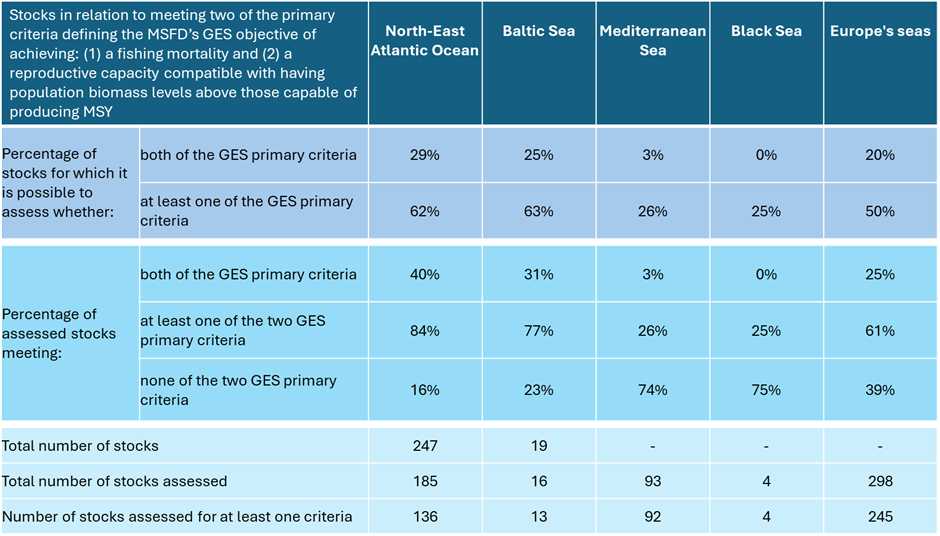

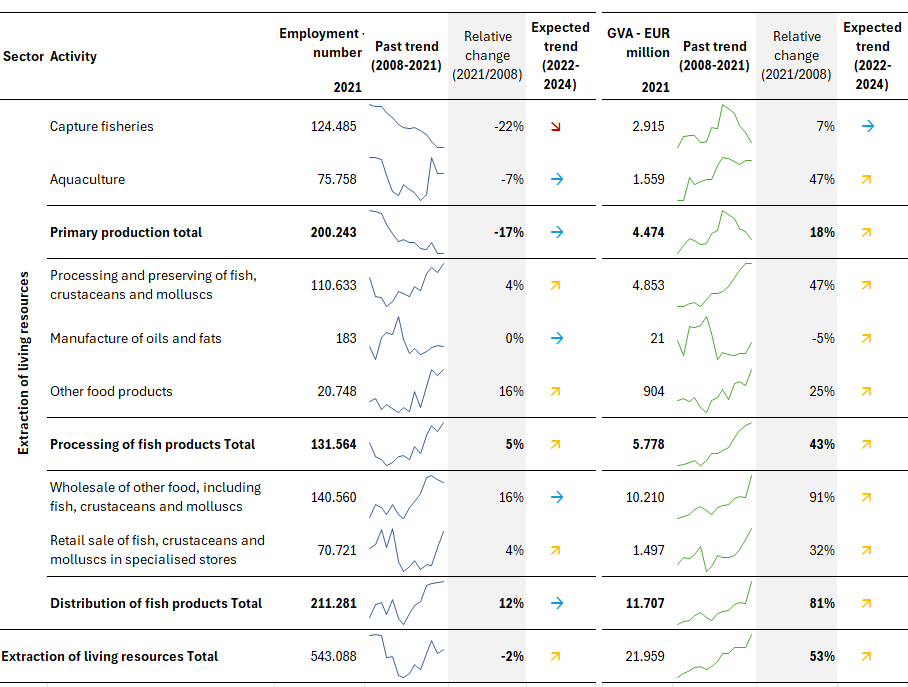

Overall, these activities generated EUR 21.9 billion in Gross Value Added (GVA) and employed an estimated 543 thousand people in 2021 (table 1).

Table 1: .

Read more on these activities

Fish and Shellfish Harvesting and Processing

Aquaculture

Pressures on the marine environment

The extraction of living resources puts significant pressure on the marine environment including:

- Physical loss and disturbance of the seabed: Bottom trawling is the most extensive human activity impacting the European continental shelf; abrasion of the seabed by benthic trawling or mussel and scallop dredging damages abiotic and biotic structures (Korpinen et al, 2019).

- Commercially exploited fish and shellfish: Commercial fishing, which aims to maximise the amount of fish and shellfish caught, impacts the populations of the target species (by their removal, changing age structures, etc.) and can also result in by‑catch, which impacts non‑target fish and shellfish and populations of other species, e.g. seabirds, turtles and mammals (EEA, 2015). It, therefore, also influences the structure of marine food webs, as well as disturbance to seafloor.

- Contamination: Aquaculture requires external inputs such as feed and medicines which pollutes the local ecosystem.

- Non-indigenous species can be introduced by vessels ballast water, tank sediments, hull fouling and as well as escapes from aquaculture and mariculture.

- Marine litter: Fishing (alongside shipping) is one of the major sea-based sources of marine litter which includes plastics (e.g. ropes, nets, etc.) and microplastics. Lost or abandoned fishing gear also has widely acknowledged effects due to ghost fishing which results in the entanglement of various marine fauna (Lopez-Lopez et al, 2017).

- Underwater noise: Both fishing and aquaculture are a source of continuous noise in the marine environment. For aquaculture this is caused by the intensive systems used such as air and water pumps (Davidson et al, 2009) while for fishing it is the vessels noise itself.

References

- ↵EC, 2016. 'A short history — aquaculture', European Commission (https://ec.europa.eu/fisheries/cfp/ aquaculture/aquaculture_methods/history_en).

- EEA, 2019c. Marine Messages II. Navigating the course towards clean, healthy and productive seas through implementation of an ecosystem-based approach. European Environment Agency, EEA Report, 17/2019: 82 pp.a b

- ↵European Commission, Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries, Joint Research Centre, Borriello, A., Calvo Santos, A., Codina López, L. et al., The EU blue economy report 2024, Publications Office of the European Union, 2024, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2771/186064

- Zimmermann, F., K. M. Werner, 2019. Improved management is the main driver behind recovery of Northeast Atlantic fish stocks. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 17: 93-99↵

- EU, 2013, Regulation (EU) No 1380/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2013 on the Common Fisheries Policy.↵

- ↵EEA, 2019a. 'Status of marine fish and shellfish stocks in European seas (CSI 032/MAR 007)', European Environment Agency (https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/indicators/status-of-marine-fish-stocks-3/ assessment-1) accessed 23 August 2019.

- a b cEEA indicator 2024. Status of marine fish and shellfish stocks in European seas. https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/indicators/status-of-marine-fish-and

- ↵STECF (2023). The 2023 Annual Economic Report (AER) on the EU fishing fleet (STEFC 23-07). https://stecf.ec.europa.eu/data-dissemination/aer_en

- a bFAO (2024). FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture - FishStatJ - Software for Fishery and Aquaculture Statistical Time Series. In: FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Division [online]. Rome. https://www.fao.org/fishery/en/statistics/software/fishstatj